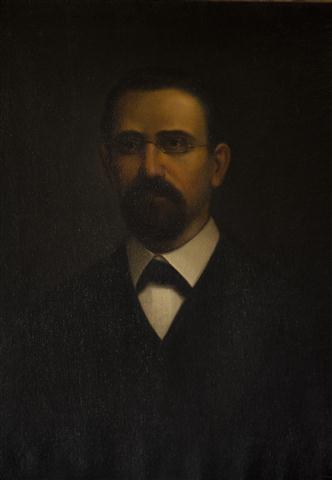

Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes: A Symbol of the Cuban Soul

Por: Magda Resik Aguirre

In the solitude of his last days in San Lorenzo, he wrote a long diary-like letter to his beloved Ana de Quesada, telling her about the rigours of his isolated shelter, convinced that the once President of the Republic-in-Arms didn’t need much to live. His little guano palm house, as he described it, was sheltered with good wood, it had two bedrooms covered with palm leaves and cedar boards where a hammock, a small table-desk, a bench, his weapons and other tools made up the universe to which his human greatness had been reduced. There was plenty of food and affection from people in the neighborhood as “there was rarely a day when they didn’t pay us a visit” – and also bathing in the stream near where the Contramaestre river waters flowed in. At this stage, his son’s love kept him going when faced with anguish: “Some consolation I find in looking at your portraits every day. I showed them to almost all the patriots who are here with me. Most of them, especially women, ask me to show them the portraits, waving their arms around with admiration and giving us a million blessings, wishing for us to be together again.” Carlos Manuel de Céspedes only begged his Ana to believe that, although maintaining her fidelity and her distance from him, her self-denial and her stoical care of twins Gloria de los Dolores and Carlos Manuel was difficult, it was also extremely painful for him to be apart from them.

Some of the great men in history have faced their destiny in solitude, shrouded in the tide of human meanness and power ambitions. Nevertheless, their magnificence invariably prospers after death and is repeated in the growing inspiration they represent for those patriots that are still to be born, – Céspedes was one of them. When he was elected President in 1869, he counted on Cubans’ heroism to seal independence and on his compatriots’ virtue to consolidate the Republic. He promised self-denial to his followers, who were quite a few, and proved that he had honored that commitment with his own life through self-sacrifice, and relinquishment of power and material well-being.

The ideals of those men of [the War of] 1868, as the generation of Creoles rising up in arms against Spanish rule is known, progressed in the discretion of Freemasonry. The Buena Fe (Good Faith) Lodge brought together the leaders of the fomenting Revolution in Manzanillo territory on 26 July 1868, as if that date was predestined in the history of Cuba. Under the leadership of Céspedes, revered Master of that lodge, light was shed on the ideas bringing together the visionary men of the Ten Years War. In those days there was “a basic knowledge catechism – a philosophical and political teaching system for people’s education and training”, consolidated on the slogan “Science and Virtue; Science and Consciousness”, which was master José de la Luz y Caballero’s emancipation thinking. The need for social equality was recognized and the dispossessed were designated as the only class to turn the people of the world into brothers and sisters. And above all, the nation was conceived within the purest tradition of the Cuban revolutionary thinking introduced by Father Félix Varela: “The nation is (…) the social and cultural core of the people’s traditions and habits and, especially, it is a source of social justice and projection toward a common, just and free future.”

A self-confessed follower of Céspedes is without doubt the Havana City Historian, for whom fascination with that outstanding figure of the national independence was reinforced when he held in his hands, after a long search, the notebook and small book containing in a diary-like manner the incidents of Céspedes’ life from 25 July 1873 to the day he died on 27 February 1874. In spite of the very small handwriting, to save space presumably, characters were clear and accurate. The tireless fighter had dedicated his notes to his beloved Anita, who was deprived of the comforting enjoyment of reading those thoughts from her man.

To Eusebio Leal, Céspedes’ greatness lies in his human condition. He was irascible and ill-tempered, and amongst the sacrifices imposed by the Revolution, the most painful one – as he confessed in writing – was that of his character. His self-willed and forceful nature, however, also led him to dare launch the independence call.

When his body fell over a steep cliff in San Lorenzo “(…) many cried over that strange gentleman who shared his limited possessions everywhere, as calmly as he had once chosen the infinitely superior vocation of a revolutionary whilst being a landlord.”

Every 10 October, Cubans of all generations gather at the foot of the statue of the Father of the Cuban Nation on Plaza de Armas square, with such discipline and devotion as is customary for those who recognize the significance of Céspedes’ legacy, and then go on a pilgrimage to the Flag Room at the City Museum. The once Captains-General Palace – like a symbol of the irreversible nature of Cuban independence- treasures the most important rebel flags, and amongst them, in a place of honor, is the flag flying at La Demajagua farm that day of 1868. The ceremony during which the original notes of the Bayamo Anthem seem to take us back in time, has become a well-established tradition for our City Historian, following another legacy full of symbolism from his predecessor Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring.

“The City Museum was re-opened in 1968 on the occasion of the first centenary of 10 October”, Leal said. “It was an agreement and a nice suggestion by our dear and unforgettable friend and comrade Celia Sánchez who, like her father, Dr. Manuel Sánchez Silveira, was also a devout follower of Martí and Céspedes. A National Commission, presided over by Commander Faustino Pérez – another important figure of the revolutionary history – had been created to celebrate the 100th anniversary. He gave me his full support and we worked hard to complete the first phase of the City Museum, which did not include what would be years later the main achievement – the Flag Room, where we go on a pilgrimage every 10 October, after tribute is paid to Céspedes at the foot of the statue erected at the center of the Plaza de Armas.”

Placing that statue at the center of the Plaza de Armas became one of your predecessor Emilio Roig’s great battles. How did the first Havana Historian win that struggle?

It was illogical that Havana did not have any monument to Céspedes – the Father of the Cuban Nation. The only one dedicated to him had been erected by two teachers – Hortensia Pichardo and her husband Fernando Portuondo – at their own expense. They used to teach at the Víbora Institute, in front of which they unveiled a modest bust.

From that moment on, a battle began – a battle waged by Hortensia, Fernando and, of course, Doctor Roig – to have a magnificent work sculpted, depicting Céspedes as some biographer had called him – the dandy hero, elegantly wearing his best clothes, like the day of his death, looking towards the future. This would involve the removal from the Plaza de Armas of the statue of king Ferdinand VII – an abominable figure in the history of, not only the Spanish monarchy, but also the international policy at that time; this was characterized by complex relations between Spain and France, Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, and Ferdinand VII’s successive betrayals to his father, the liberal movement and the military loyal to the national independence cause. Finally, he was the man who so cruelly suppressed the whole Spanish and American progressive movement of his time.

Many people – including some intellectuals and historians – however, did not support Doctor Roig’s act. A complete file containing all the criticism against him about the dilemma of the historical monument to Ferdinand VII that should stay where it was, still survives. Roig defended himself fiercely and placed the monument there anyway, because he knew that at that time the king was still symbolically in power in Cuba, represented by a vicious, corrupt, decadent and criminal tyranny. When he decided to place a Céspedes statue there, he was looking for something symbolic of the Cuban soul. Then the statue was put in its place, yet Ferdinand VII’s statue was not destroyed and Roig decided to keep it in the Museum.

When I was faced with the dilemma at the time of the Plaza de Armas restoration – through which the essence of the original square was being rescued -, it was impossible that, in the name of any principle, the Ferdinand VII statue could be placed back where it had originally been. Perhaps if the debate had occurred today, the statue would still be there, because Céspedes already belongs to all Cubans and he deserves a greater monument. This is how I responded to Carlos Rafael Rodríguez when he asked me about that matter, because he had witnessed that debate that had hurt Emilio Roig so deeply. Then the Ferdinand VII statue was placed in a corner of the square with the same stone plaque that Dr. Roig had written to have it displayed later. The plaque fully explains what happened and no visitor can help stopping and reading it. This is a permanent lesson that my predecessor gave us all, because it is better to provide an explanation of monuments and history rather than hiding them.

Which were Céspedes’ personal conditions and circumstances of his life that made him the man of the Independence Revolution? Why him and not anyone else?

Man’s role in history is only denied by the small-minded. Céspedes was the leader of that movement and he earned such leadership, first, because of his background. Let us remember that he was a man of culture; he could speak six languages. At the age of eleven, he began translating, for example, the songs of the Aeneid from Latin – and he made an excellent translation. As a lawyer, he had studied Latin, Greek and English, and he could speak perfect French and Italian, which allowed him – once he concluded his major in Barcelona where he earned a Lawyer of the Kingdom degree – to undertake a long trip to England, France, Italy, Turkey…

An interesting event has recently occurred – the discovery of a reproduction on an engraving of a probable painting showing an unusual meeting of Céspedes, Avellaneda, the countess of Merlin and others in Paris. If this is true, we then find a man who was highly motivated by the most advanced thinking and Cubanness of the time. Céspedes was an excellent horse rider, a good fencer and a chess player who usually finished the game with his back to the chessboard, which he knew so well. He was a passionate speaker. When he was allowed to practice law in Cuba, on his return to Bayamo, he became one of the most-requested lawyers advocating certain causes. I must remind you that he had previously studied in the capital – at the St. Charles and St. Ambrose Seminary, and at the University of Havana, which means that he had been at the two places where Cuban thinkers had their discussions in this city. And every day, on his way from the University to the Seminary, or the other way around, he would walk past the Art and Literary College where the cream of our country’s intellectual circles used to meet.

Since 1850 he was regarded a dangerous man by the Spanish authorities – someone who frequented cultural gatherings disguising a political project. He was imprisoned on several occasions – in Manzanillo; he was exiled to Baracoa; in Santiago de Cuba (El Morro), in the wet chambers of the warship Soberano which was anchored in the port of Santiago as a relic of the Battle of Trafalgar.

Finally, the Freemason loggias began to be founded. Freemasonry was the most progressive and freedom-loving institution of the time. The great liberal – and I would say almost romantic – legacy of freemasonry which hoped to see a slave-free Cuban society, is expressed in Céspedes’ autobiographical poem entitled Contestation. I missed that detail – he was also a poet. And poetry and literature had a significant influence on the forging of a national sentiment: Heredia, Avellaneda and those around Céspedes – José Fornaris and Francisco Castillo- were poets. La Bayamesa, which is Cubans’ Song of Marseille, was created by the three of them.

Céspedes was related to another key figure in our history – Pedro Figueredo – and to another great gentleman whose name was Francisco Vicente Aguilera.

An important lodge called Buena Fe (Good Faith) was created at that time – this was before the uprising – whose members were not only Cuban but also Spanish Liberals longing for a change in Cuba. It is very likely– though debatable – that the uprising was planned to take place on a specific date, but it was postponed over and over, waiting for the right circumstances. Finally, an agreement was reached: if the conspiracy was uncovered – like almost all conspiracies – the first one to rise up in arms would be followed by the others.

And it occurred that the conspiracy was indeed uncovered and Céspedes was the first one to rise up in arms?

That is a hypothesis.

Is it true that the moment of the uprising may have also been motivated by the fact that this was such an important date for the Spanish Crown?

Queen Elizabeth II’s birthday was on 10 October and this date was an official holiday celebrated from the Captaincy-General of Havana to the last government representative of the interior of the country. Previously, during another celebration on the occasion of the princess of Asturias’ birthday, Céspedes had organized a ball that was regarded as a defiant attitude toward the authorities, – and one for which he was accused. Proceedings were initiated because, for that occasion, a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II had been borrowed, and ended up like the one that had been placed at the University of Havana – it was torn. A few hours before 10 October, on the Queen’s birthday, an insurrectional movement had been detected. The Governor of Oriente had been warned by various political and military chiefs that the sound of bells, spurs and machetes could be heard in that area. There were rumors that weapons had been bought and unloaded through a specific point; a lot contradictory information was generated. Actually, they only had a few weapons. In a memorable conversation he had said to the other person: “the weapons are with them”, -in a call to snatch them from the enemy. Finally, on the eve of 10 October, the Captaincy-General ordered that anyone suspected of being involved in the conspiracy be arrested. It is thus that Céspedes decided on 10 October.

To me it may be a wonderful coincidence or something customary for someone as clever as he was that, in a prior meeting held in one of his favorite places – San Miguel del Rompe – he said that Spain’s power was outdated and worm-eaten, because for centuries they had looked at it on their knees. “Rise up!”, Céspedes cried out. This means that that was his will – against some of his comrades’ opinion – since they said that it was necessary to wait for the next sugarcane harvest to be able to buy weapons and supplies. That was perhaps a prudent policy, recommended by conspirators in Havana who had promised their support. They were basically reformist groups who were frightened by López’ conspiracy actions in 1849, 1850 and 1851 and did not lift a finger to help him; they took part in the conspiracies, but left him alone in the end. For the first time, and with a view to achieving independence and the abolition of slavery, there was an actual uprising unlike all the others that had taken place before. What was logically not clear in 1849, 1850 or 1851, was perfectly clear to Céspedes in 1868. His lucidity was based on a highly educated man’s qualities, a young man who, despite his young age – he was 50 years old -, was one of the most senior chiefs among those rising up in arms. Immediately after the uprising in La Demajagua farm, others followed in various points of Manzanillo, Jiguaní and the whole eastern area. People rose up, armed parties joined and soon the fires of revolution were burning and were given the name of Grito de Yara [a proclamation of independence].

Why was the Revolution named after Yara and not La Demajagua?

Hortensia Pichardo asked herself the same question and we discussed it on several occasions. Céspedes himself provided an explanation in his last diary. He said that on that early morning, leaving La Demajagua where those responding to his call had gathered, they headed for Yara, the place where the first incident with Spanish troops occurred. Then there was an exchange of shots, confusion – some say it was raining -; the truth is that for a moment Céspedes was left with a handful of people – reportedly 12 – and with the flag that Candelaria Acosta (Cambula) had embroidered at the farm. It was a different flag from that of Narciso López and Joaquín de Agüero (the flag that had accompanied them on their 1849, 1850 and 1851 expeditions). Céspedes’ motives to change its design – when no one could forget that other flag – remain a mystery to me. Later, a decision was made in Guáimaro to have López’s and Agüero’s flag as the national flag. Nevertheless, in order for Oriente [the eastern side of Cuba] and Céspedes – who had been the first one to rise up – not to feel offended, Céspedes’ design – like that of the Republic of Chile with inverted colors – would preside over the House sessions, and the Cuban Congress at a later date.

By Agreement No. 1 of the National People Power Assembly, both flags are flown during its sessions. Céspedes is also present whenever we sing our national anthem. On 20 October, after the city of Bayamo was taken, Pedro Figueredo introduced the music he had composed – a sort of synthesis of certain melodies that were very important and even popular.

Professor Manuel Duchesne Morillas – father of Manuel Duchesne Cuzán – told me that some antecedents could be found in the Cuban anthem. It showed great patriotic inspiration and was composed with no lyrics to accompany the Corpus Christi procession at the Bayamo Church. The Song of Marseille could be furtively heard in the background; a little bit – as Duchesne put it – of the Barbero de Sevilla (the Barber of Seville) and finally, during the fight, it became what it is today – a great revolutionary march and the National Anthem of Cubans. However, it did not have any lyrics.

On 20 October, after Céspedes himself interceded for those who were under siege in Bayamo city to surrender, the first capital of the Revolution and the first revolutionary town council were established, and Céspedes made sure that non-white people who had been completely discriminated against until that moment, were

for the first time nominated and included.

Let us not forget that on 10 October, in his farm La Demajagua, where the best sugar cane was produced and he had managed to rebuild his once destroyed fortune, he had salary earners; that is, he was already moving towards a superior form of production; slave production gave way to capitalism – the most revolutionary form at that time, which was introduced late in our country for it was a slave society. Céspedes had wage-earning labourers; but in all his farms, according to existing data, he had 53 slaves who had been purchased by him together with the title of Venecia house in Havana in exchange for La Demajagua farm, situated in a privileged location facing Guacanayabo Gulf with the mountains at the back. There were only a handful of slaves in the farm, enough to become a symbol of Céspedes’ will when they were set free by him – the powder was lit.

The farms that were the property of Céspedes and other families who were also involved in the conspiracy were located on that site. Names such as Francisco Maceo Osorio, Titá Calvar and Jaime Santiesteban were among those who came out that day.

Francisco Vicente Aguilera could not join them, because he was surprised by the news in his Cabaniguán ranch and from there he came with all his hunters, with all his people, throwing one of the largest fortunes in Cuba to the fire, after he had put everything up for sale. He was the wealthiest man of all. He was called the Herald Without Glory, because for a long time historians focused on purely personal matters and did not see the social process involved in the Revolution, nor did they notice the great contribution of the armed uprising to political ideas. They rather dwelled on personal conflicts that were only purified over time and conquered by the Revolutionary tide. Unity – the dream most nurtured by Céspedes, that man who was able to rise up in 1868 – was finally achieved in our day, thanks to Fidel Castro’s work. Céspedes has been accused of being everything: a tyrant, an aristocrat, an elitist… What his detractors – past and present – cannot take away from him, is his nature as a precursor and his ability to fight. Céspedes – like Maceo – did not smoke or drink; he was never heard uttering any imprecations or insult. He was refined and sharp as a knife in political arguments and was never a vulgar adversary. Only in the secret pages of his diary did he use the most severe terms.

According to some historians, there was a moment when he sacrificed his leading role in the Revolution to that necessary unity. Do you share that view?

He was removed from his post when the House was no longer represented by the illustrious men from Guáimaro and then some sort of idealism, analyzed in depth by Enrique José Varona, emerged – idealism that sometimes was far away from reality, even though it was pure and had noble aspirations. The reality was – and Céspedes said so – that every speech and meeting was a waste of time, and what they had to do was fight to win. That was his vision. And he was also an idealist. Céspedes was the one elected President of the Republic formed in Guáimaro – and it could not be otherwise. However, in the name of idealism being afraid of tyranny, as Martí himself described it, – fear of Caesar or Alexander’s Generals – he agreed to subordinate the executive to the legislative power; that is, the President to the House [of Representatives]. That explains why Céspedes was not only the President, but also the leader of the Revolution and did not require any title to be so – he simply was! Nevertheless, he gave in.

There are those who have seen a generational struggle in that political moment. Like I said, Céspedes was part of those events at the age of 50. It is embarrassing to have lived much longer and to think of the times he lived in. And in those arguments, he gave in. He gave in to the flag – as it was the flag with which they rose up in arms – so that it was placed following an idea in his manifesto: “Cuba wants to be free and independent to hold out its hand to all the people around the world.” In addition, he also did the tremendous act of freeing his own slaves – which was like adding fuel to the fire. He had seventy something slaves in La Demajagua.

There was also a very important man – José Joaquín Palma – a friend and first biographer of Céspedes. This biography, in which he said that a free Cuba could never again be enslaved or have any slaves, was proofread by Céspedes himself. That was the concept, rather than the text.

Therefore, there cannot be the slightest doubt that the democratic criterion of this doctrinarian idealism prevailed in Guáimaro, sometimes a little bit delirious and alien to reality.

How much impact could the antagonism between Céspedes and Agramonte referred to by some people have?

Those who lit the fire of conflict always wanted to see Céspedes as opposed to Agramonte. And that is not true. They both had similar births. When you go to Camagüey, Agramonte’s house was the most important in town. It was a two-story house – a palace opposite La Merced Church; but Céspedes’ house – the one that still survives – is also a magnificent mansion in Bayamo. The column and porch house that was his residence and office is burned beyond repair. They both had a lot to lose and sacrificed everything for their ideals. That is the first thing of note.

They both studied in similar academic environments – at the Royal and Pontifical University of Havana, with its cultural atmosphere, including the Seminary, where they went to attend class, talks and master lectures given by intellectuals at the old University site. It was precisely at this University – a secular university back then – where their important voices would be heard. Later Céspedes went to study in Barcelona – and so did Agramonte. That city was the place where the most economically advanced people in Spain lived at that time and there was a big autonomist and pro-independence movement. By the way, the Catalan flag was inspired by the single-star flag. They were both lawyers. In a country like Cuba, the two determining professions have historically been Law and Medicine. Céspedes, Agramonte, Martí, and Fidel – all lawyers.

There was a clash between them. That was inevitable. It did exist. There was even a time when Céspedes decided – out of gratitude, I think – to help Agramonte’s family, and requested an orphan’s pension for them, to which Agramonte responded… The same thing happened around Céspedes: there were always coryphaei, courtiers who enjoyed sowing the seeds of discord and perhaps they actually did, to such an extent that something unusual occurred – Agramonte challenged Céspedes to a duel, which was a terrible thing because Céspedes was the President of the Republic at that time; a President being challenged to a duel by a Major General of the Army was not only unconstitutional but also an act of rebelliousness. However, how did Céspedes handle this? His understanding of Agramonte’s hurt feelings was so deep because of what he [Céspedes] had experienced himself. And how was it settled? And how did Céspedes react when Agramonte resigned from his leadership position, to which he was so gifted?

Agramonte is like Sucre in this story – the second-best prepared man after Céspedes, because he had the four qualities: cultural knowledge, knowledge of Law, his aspiration to achieve democracy and the worship of freedom. He was younger and died at the age of 31. Agramonte was exceptionally articulate. He became a military chief capable of doing tremendous things, such as the Cocal del Olimpo combat or Julio Sanguily’s rescue – an act of extreme valor. He was also a highly respected man and a great organizer. He had organized the war in Camagüey, the factories, prefectures to provide the army with supplies … At this stage the [eastern] region still played a determining role but very few were able to take things further. That is why when Agramonte returned and was appointed by Céspedes as chief of Camagüey and Las Villas, amends were made for the past; Agramonte then took up the leadership of the Revolution in Camagüey, where the enemy had wrought havoc and freely persecuted many people – the city had been virtually turned into the enemy troops’ headquarters, and Cuban families and those with strong ties in the region like his own, were being persecuted and humiliated.

The biggest humiliation was to bring his corpse to Camagüey and have it burned at San Juan de Dios Square – that was the last straw, and is still remembered. When Agramonte was appointed by Céspedes for Camagüey, the bishop was returned to the chess game.

Agramonte’s death was Céspedes’ death, because the former died first. Had Agramonte been alive, I think Céspedes would have not been removed from office the way he was; Bijagual, the geographical place where Céspedes was overthrown by the House [of Representatives], would have not existed. Today that site has been erased from the map. It is now covered by a dam named after the Father of the Cuban Nation.

Those were like the waters of the River Jordan – very bitter days. And then the Revolution that had succeeded in freeing the popular classes began to be destroyed – a Revolution whose major achievement had not only been to unshackle slaves but also popular classes.

And that meant a delay on the definitive Revolution.

It meant a delay, but it was only a matter of time. Spain had come to stifle the Revolution with a number of resources, but had not been able to gather everything it required. That is why the timing was so decisive. Céspedes explained his vision to Máximo Gómez who, though still resentful, did not hesitate to acknowledge that it was that leader who had given him the idea that without an invasion to the west of Cuba, going beyond the frontier that had been established in the centre of the island, even if a million men were placed on the eastern side, Cuba would never be free.

Which was the fighting strategy proven in 1895 and then definitively in 1959.

In the Las Guásimas battle, at the gates of Camagüey, the advance of a contingent led by Gómez heading west was halted by a Spanish column and the latter won what could be called a Pyrrhic victory. The Spaniards managed to go back to Camagüey but had significant casualties and the Cuban rebels could not prevent the Spanish troops from getting reinforcements from that city. The only shelter left for pro-independence fighters with all of their casualties and with their munitions running out, was the woods.

And like any political man, Céspedes was not infallible. I should not be the one analyzing any mistakes here, because just imagine, what can I say when only those who live in the spiral of war have the right to express an opinion. You have to go into history with your head exposed and showing respect. But every piece of history has light and shade, and those figures receiving the biggest amount of light also project the largest shade. Now then, those zones of semidarkness need to be carefully studied. You need to see the light first – and light is fire; first you have to see the fire and be prepared to get burned. You cannot see the 10 October process from the outside where you do not get splashed with blood or mud.

When Agramonte died, the Revolution succession died with him, and the rest was like a ball coming down the mountainside. Céspedes was removed from office and immediately afterwards, a fragile succession of the Revolution leadership began, but all it did was clash with reality.

Finally, the big crime: solitude in San Lorenzo and what happened up there on the top of the mountain on 27 February 1874 – that is, Céspedes’ death. Before that, his family tried to rescue him and came up with a plan to search for him. He hesitated, and eventually accepted his fate, which also meant accepting glory.

The 10 October man could have not died in the United States or Jamaica, where his brother Manuel Hilario and his sister Francisca de Borja (Borjita) were; the 10 October man could not forget his brother Pedro… When Pedro de Céspedes was shot in Santiago de Cuba, Céspedes turned up at the House [of Representatives] to see the Governor of Oriente [eastern side of the country], who had arrived in November 1873 with the Virginius expedition, and told him that as his brother and nephew-in-law Herminio – who also came on the expedition – had died, he would once again put his life at the service of the revolutionary cause. That is when the giant began to grow.

The pieces of the story come together when we remember that he sent some pieces of his own hair to his twin children who were born in the United States to Ana de Quesada – Gloria de los Dolores and Carlos Manuel; or when we learn that he sent the 10 October flag in a small document tube inside a box that was intended to save the banner (which today is on display in the Flag Room [at the Havana City Museum] ) and later returned to Cuba by Ana de Quesada herself, soon after the unfortunate 1902 Republic was proclaimed).

Finally, the Old President – as he was called by farmers – wandering around the part of the mountain where he was held captive, in a place called San Lorenzo, with no other escort than his own son, some loyal people accompanying him and a few locals. Now, what an amazing thing! Céspedes was wearing just any clothes, rather grotesque as he put it, but he didn’t need anything else. So he wrote to his wife when she offered to send him clothes and he refused, because he had learned to do without anything. In his diary, he confessed that he was crossing the river one day and dropped a silver spur that he had worn since the beginning of the Revolution, and was pleased to see that he was poorer every day.

All his past nobility – as described by Martí – the elegant clothes, the diamond ring, the tortoiseshell and gold cane; all were gone. What was left was a man who, whilst still young, rode or walked on exhausting journeys around the mountains, religiously coming down for a swim in San Lorenzo pond.

It is amazing to see how well preserved that place is. Celia Sánchez ordered that site to be preserved. On her instructions, a bust of Céspedes was placed on top of the crag from which he fell. Biographers, Hortensia herself and Rafael Acosta, evade the suicide issue. When asked by Ana de Quesada what her husband’s body looked like when he was taken out of the gully and shown in Santiago de Cuba, Leonidas Raquín – Céspedes’ confidant in Santiago de Cuba – referred to a small wound he had in his chest and his slashed clothes, which, to my mind, did not match a point-blank range shot by his pursuers.

He maintained that all the bullets in his revolver were meant for the Spaniards, except for one that he kept for himself, if at the last moment he was taken prisoner or humiliated by the enemy, because it was the Revolution – not just him – who would be taken in chains to Santiago de Cuba, and subjected to humiliation, as Pedro Figueredo was. The latter, however, right before he was executed, said that he would be with Carlos Manuel de Céspedes either in glory or death. So, an extreme act by him would have not been unworthy of his character.

The Father of the Cuban Nation fell into the gully and his corpse had to be recovered. The image – as described by Cintio and Fina – of his son arriving home after he heard the shooting in the mountain, only to realize that his father was no longer there. Then he followed his father’s trail of blood and strands of hair, picking them up on his way down the hill. That image followed the tracing planted in Cuban soil, which, according to José Lezama Lima, is the right fertilizer for a nation to be born.

If the man from Yara and La Demajagua had died in the United States with his family, he would not be the Father of the Cuban Nation – he would be an anecdote – the initiator, and nothing else. But his sacrifice in San Lorenzo, his observance of the law, his oath that no Cuban blood should be shed because of him, his statesman’s vision of the future, made him so.

And what did he do in San Lorenzo during the last days of his life? He spent hours teaching farmers’ children how to read and write with a booklet. On the day he died, he opened his trunk, took out the elegant clothes that he had kept and put on his best outfit. Everything is written in his diary. A few hours before, he had a premonitory dream where he realized – as the hypersensitive and intelligent man he was – that the end was near. And the end came on 27 February 1874 when he fell off the crag, and Manuel Sanguily – whom I should quote – wrote: “he fell into the gully like a brazing sun sinking into the abyss.”

How much can Céspedes continue to save us today, and serve as an inspiration to us as a nation?

Our true savior is looking into our past, which is also everything that is taking place right now and is being left behind. We should look into such remote past and find the foundations of our nation. We cannot just accept a fragmented thought or slogans; we should look for the essence of things.

Many stories and biographies have been written by Leonardo Griñán Peralta, Antonio Aparicio, Herminio Portell Vilá, Hortensia and Fernando with their imponderable three-volume work; Cintio Vitier and Fina García Marruz’s work quoted by Lezama on several occasions in his wonderful paper about Céspedes; Rafael Acosta, whose beautiful book The Broken Silence of San Lorenzo I am now reading at nighttime – and for which I wrote a prologue – carries out deep analyses that are essential to understand Céspedes today.

Salvation lies in observing not only individuals’ histories, but the history of the process and how such process and heroic deed serve as an inspiration to the birth of a nation, and definitely resisting the temptation to sanctify or idealize those individuals to such an extent that their exploit becomes impossible to be imitated by new generations. They were men and women like us. What happened was that at the time they were called by fate, either due to their own determination or circumstances, they became exceptional people. That is the truth. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y López del Castillo – the Father of the Cuban Nation – was an exceptional man.

(1) Speech by Eduardo Torres Cuevas during the Cuban Academy of History Session on the 143rd Anniversary of Céspedes’ uprising at La Demajagua Farm.

(2) Ibidem.

(3) Leal Spengler, Eusebio. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. El Diario perdido (The Missing Diary). Publicimex S.A., La Habana, 1992, p. 15.

(4) Extracts from the stone plaque writing: “Ferdinand VII. His kingdom was an example of shamelessness and absolutism. In 1821, he pretended to abide by the Cadiz Constitution in the face of people’s pressure to immediately burst through with the most sanguinary reaction. (…) Until his death in 1833, Spain lived an era of indescribable despotism. (…) This statue was placed at the Plaza de Armas (Parade Ground) in 1834 and removed from its pedestal on 15 February 1955, after a tenacious struggle led by Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, to be replaced with that of the Father of the Cuban Nation Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y del Castillo on 17 February that year. Since then, the statue of Ferdinand VII was kept at the Havana City Museum and was placed on this site on 8 May 1975.” (…)

(5) Elizabeth II was sworn in as princess of Asturias in 1833 (at the age of three) and proclaimed queen when her father died that year.

(6) Reference is made to the meeting held on 4 August 1868 in San Miguel del Rompe – known as Convención de Tirzán (Tirzán Convention), a symbolic masonic term – where Céspedes showed his conviction that the necessary conditions were given for an armed uprising against the colonial government.

(7) In his speech, Céspedes speaks about the opportunity for an uprising in San Miguel del Rompe on 4 August 1868: “Gentlemen: Time is solemn and decisive. Spain’s power is outdated and worm-eaten. If it still seems strong and big to us, this is only because for over three centuries we have looked at it on our knees. “Rise up!” Taken from Leal Spengler, Eusebio. El Diario perdido (The Missing Diary). Publicimex S.A. La Habana, 1992, p.32.

(8) The original flag flying during Céspedes’ uprising was brought back to Cuba by Ana de Quesada, his widow, and is now on display in the Flag Room at the Havana City Museum, former Captains-General Palace, together with the official delivery deed.

(9) Reference may be found in the book titled Aguilera, el precursor sin gloria (Aguilera, the Herald without Glory), vol. 2, Bachiller y Morales Library, Pánfilo Daniel Camacho Sánchez, Ministry of Education, 1951.

(10) Céspedes entered the Royal St. Charles and St. Ambrose Seminary in 1833. From 1835 to 1838 he studied at the Royal and Pontifical University of Havana.

(11) The following is how Liberating Army Colonel Manuel Sanguily described the Father of the Cuban Nation’s death: “Céspedes could not consent to being taken by the Spaniards in triumph, as prisoner and tied up like a criminal, because he was the sovereign incarnation of sublime rebelliousness. For a short time he accepted his people’s great combat alone: he faced the approaching enemies with his revolver and, fatally wounded by an enemy bullet, fell into that gully like a brazing sun sinking into the abyss.”

Compartir